Key painters of French Impressionism, they had an intense and stormy relationship, worthy of a novel: they were friends, accomplices, rivals and enemies.

Their intense and contradictory friendship revolved between admiration and indignation. A unique exhibition of two geniuses on both sides of the Atlantic:

“Manet – Degas” from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (March-July 2023), travels to the Metropolitan Museum in New York (Sep. 2023-January 2024).

Only two years apart, Edouard Manet (1832–1883) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) were close friends and antagonists. 150 paintings and works on paper offer us a new look.

Their self-portraits had not been shown in decades, as if they were by Dorian Gray, not debased, simply frozen in time to avoid new quarrels. They had a mysterious relationship, since hardly any documents or letters are preserved that give us light.

They met at the Musée du Louvre, in front of a Velázquez: Infanta Margarita. Manet noticed Degas, who was copying the painting, and introduced himself, telling him that he was also a painter.

They were born in Paris in similar environments. A privileged social condition will determine their lives and works. Manet, in the upper bourgeoisie and Degas, from an aristocratic family.

Manet was the grandson of a diplomat and his father worked in the Ministry of Justice. His maternal uncle taught him art, introducing him to drawing and to Musée du Louvre. His father wanted him to study Law. To avoid this, the young man tried to enter the Naval Academy. He failed but his desire to sail was so great that he enlisted on a merchant ship and traveled to Rio de Janeiro. He returned to Paris, confirming his dream of becoming a painter.

Degas began his studies in Law, but soon devoted himself to painting thanks to the comfortable family economy and the approval of his father, whose culture and artistic sensitivity were key in his life. He was a student of Louis Lamothe, follower of Ingres, and at Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.

Degas’s aristocratic origins allowed him to discover art collections of the Parisian upper class. He was trained in the classical tradition, as an autodidact, traveling throughout Europe.

In Florence, in the home of his uncle, Baron Bellelli, Degas had access to original paintings by Boticelli, Raphael Sanzio, Mantegna, Ghirlandaio…

His father organised musical evenings in his own home. The young man was fascinated by music, dance and theatre, the favourite themes that inspired his pictures.

Manet also completed his training by traveling to Italy, Holland, Germany and Austria, where he copied the great masters.

He visited Spain, dazzled by its customs, folklore and the world of bullfighting. His passion for everything Spanish, his visit to the Prado Museum and his admiration for Goya and Velázquez, deeply influenced his painting.

He coincided with Degas, both students at Ecole des Beaux Arts. Manet copied tirelessly, choosing paintings from the Renaissance and his favourites: Velazquez, Rubens, Titian and Franz Hals.

Both young men were called up and fought on the front lines of the Franco-Prussian War. Degas returned to Paris and frequented the Opera Ballet, painting his legendary dancers.

He participated in the first Impressionist Exhibition where his paintings were applauded for his perfect mastery of drawing, understood as an analysis of reality.

Manet started out very differently: he painted genre themes, beggars, rogues, cafe characters, bullfighting and Spanish scenes like Guitarrista or Lola de Valencia. He was incorporating scenes from Parisian life, such as Música en Tuileries.

He married the Dutch Suzanne Leenhooff, his piano teacher. They had been living together for years and had a son, Léon Edouard Köella.

Degas lost his mother when he was 13. He never married and there is no known love relationship. I would have suffered throughout my life from the fear that my wife would say about my painting: “It looks pretty.”

He was a shy, sensitive and withdrawn young man, with a great inner life and difficulty in relating. Like Van Gogh, he we could psychoanalyse him through his series of Self-portraits (1854- 1858), influenced by the classicism of Ingres.

Manet had a fascination with the female nude, scandalising all of Paris.

In his first exhibition he showed two explosive works for the time: Lunch on the Grass, a picnic with a naked woman, accompanied by two dressed men. It was harshly attacked by critics. His famous canvas was rejected by the official Paris Salon but exhibited at Salon des Refusés.

Later he presented another painting, causing a larger scandal: Olympia, a nude portraying a well- known prostitute as if she were Titian’s Venus.

“Each new painting is like jumping into the water without knowing how to swim.”

Emile Zola came out defending his art in the newspaper Figaro. He was also supported by impressionist painters: Degas, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro.

Manet painted Bar de Folies- Bergére (Courtauld Institute Galleries, London) and The Amazon (Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid). Finally, the Minister of Fine Arts awarded him the Legion of Honor.

His premature death, at age 51, deeply impressed Degas (1883). When Manet died, Degas dedicated himself to searching for and repurchasing many works by his friend and rival. He even considered creating a Manet Museum.

Only then did he affirm: “Manet was greater than was thought.”

It was a posthumous, almost “bullfighting” recognition. Their artistic rivalry became a total friendship, perhaps too late.

Both were extraordinarily prolific. Manet left a legacy with 400 canvases, pastels, sketches, watercolours… currently in the best museums in the world. His painting style influenced many later artists.

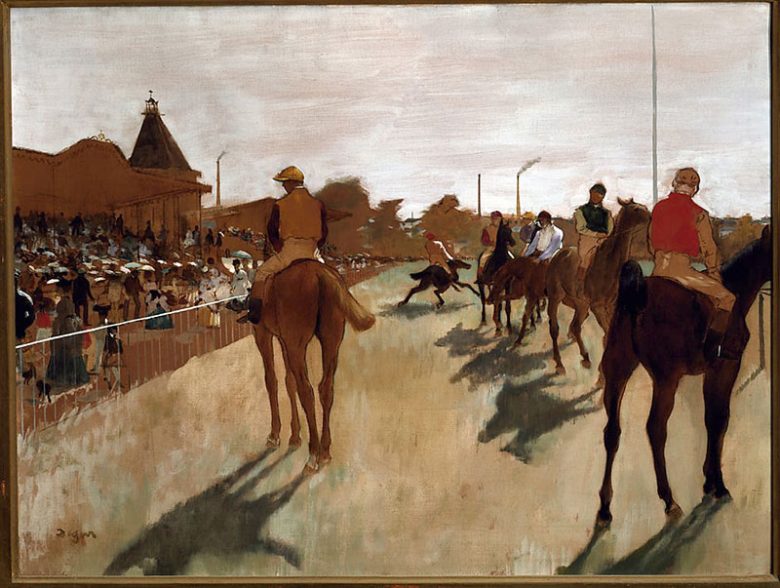

Degas created paintings, drawings, pastels, etchings, engravings and sculptures in clay and bronze. During his 60-year career, his recurring themes were dancers, nudes and horses.

He learned from artists of the past and from his contemporaries. He was deeply influenced by the Romantics Ingres, Delacroix and the impressionist Paul Cézanne.

He tried all the techniques in a process of constant exploration. Degas invented an oily pigment, “l’essence”: mixing colour with oil and paint thinner. But his vital contribution to art was his original compositions, cutting scenes and even figures. He was inspired by the first Japanese prints that began to arrive in Paris and created a decorative trend called “Japonisme”.

“There are no lines in nature, only areas of color, one against another.”

Several pairs of works show parallels such as lonely women in Cafés: Absinthe Drinker by Degas (Musée d’Orsay), Plum Brandy by Manet (National Gallery, Washington), and Hippodrome scenes: Longchamp by Manet (Chicago Art Institute) and Degas Races (Musée d’Orsay). A work that was cut into pieces and dispersed after Manet’s death is on display. Degas managed to buy the pieces and restore it: Execution of Maximilian (National Gallery, London).

There are two portraits by Degas: Bellelli Family and The Manet Marriage (Kitakyushu Museum, Japan). It was his gift to the couple although Manet cut the canvas because he did not like how Degas painted his wife. He angrily took it back, which marked the initial breaking point of their friendship.

Manet, was the least impressionistic of the impressionists, obsessed by fame and success, overwhelmed by insecurities, he reflected his political impressions in his works, something that Degas never did.

It was yet another provocation to their inevitable growing rivalry. His artistic personalities were so strong that they finally clashed.

They had a very intimate relationship, admiring, envying, getting angry… as Matisse and Picasso would do years later.

They spied on each other and this connection greatly boosted his artistic production.

Manet and Degas painted the Parisian Belle Epoque and in their mutual observation, their creativity grew and competed, to adopt new independent and very different nuances.

The exhibition is curated by three museums: Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Musée d’Orsay and Musée de L’Orangerie (both in Paris) and sponsored by Rosalind & Kenneth Landis Foundation and Sam & Janet Salz Trust.

The “Manet – Degas” exhibition brings to light one of the most interesting artistic dialogues in modern art, with its lights and shadows, both on the pictorial and personal levels.