Constructivism: the art of building a new world

Constructivism was not just an art style. It was a call to build a new, modern society.

In the wake of cultural and political revolutions in early 20th- century, a radical art movement emerged from Russia.

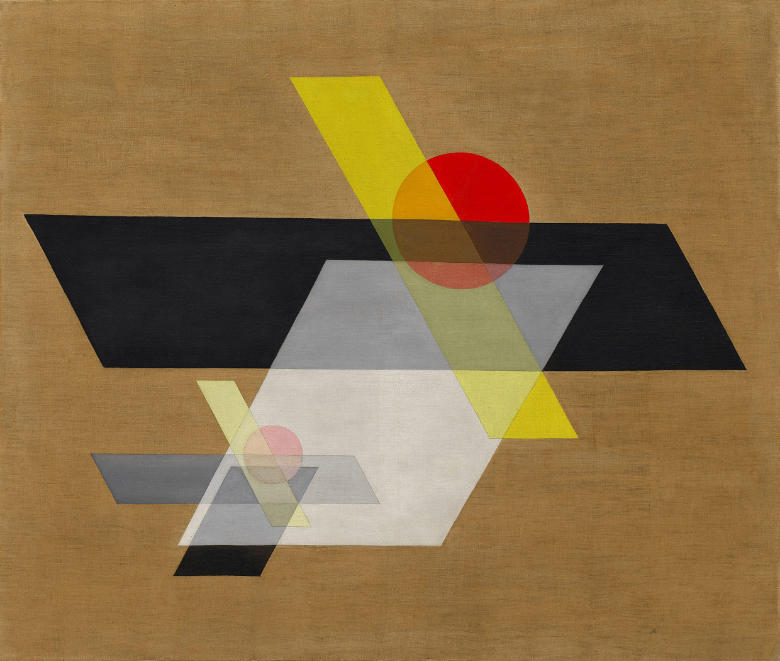

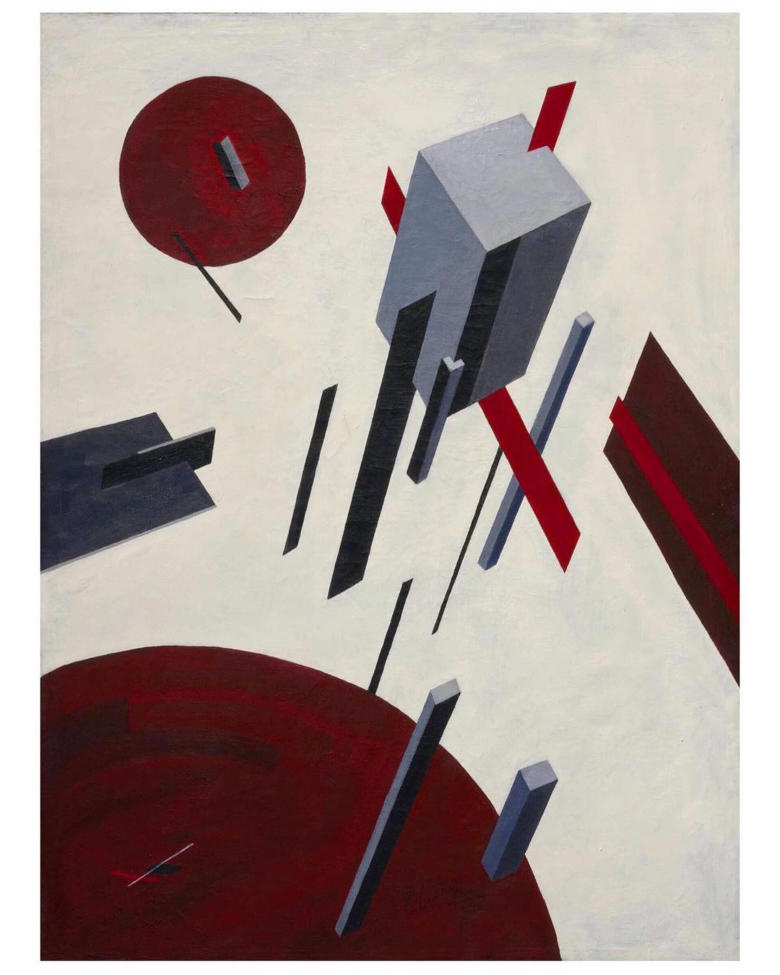

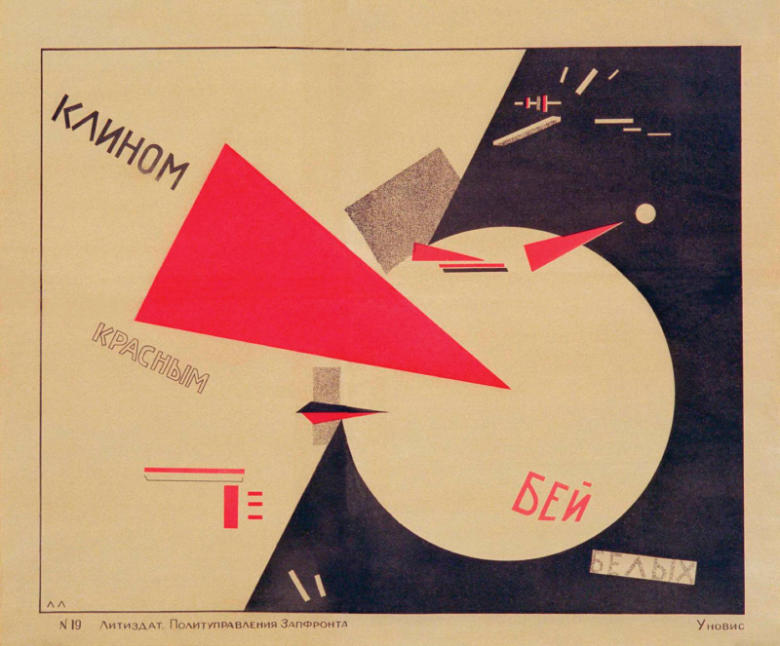

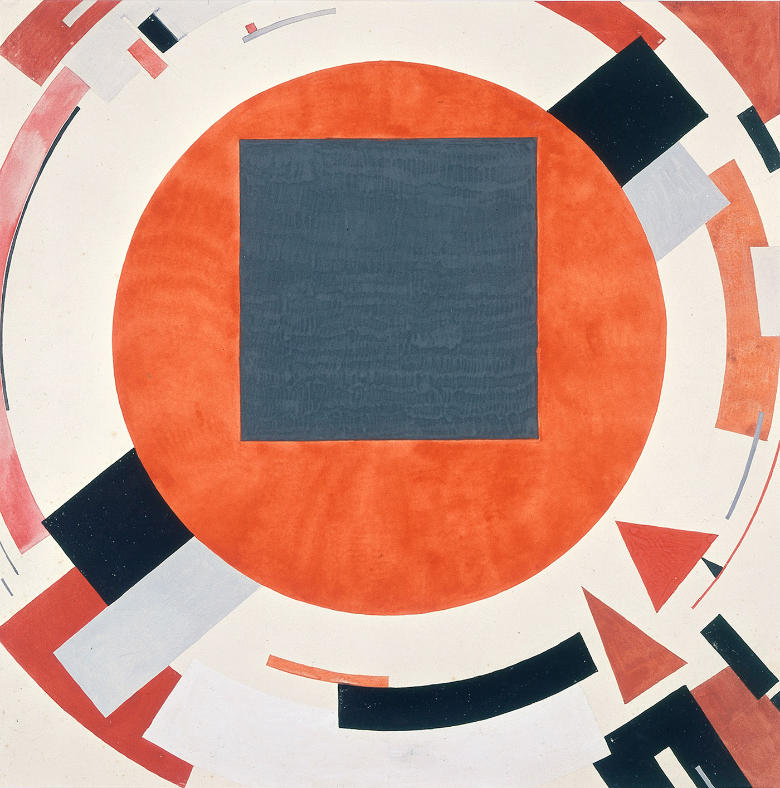

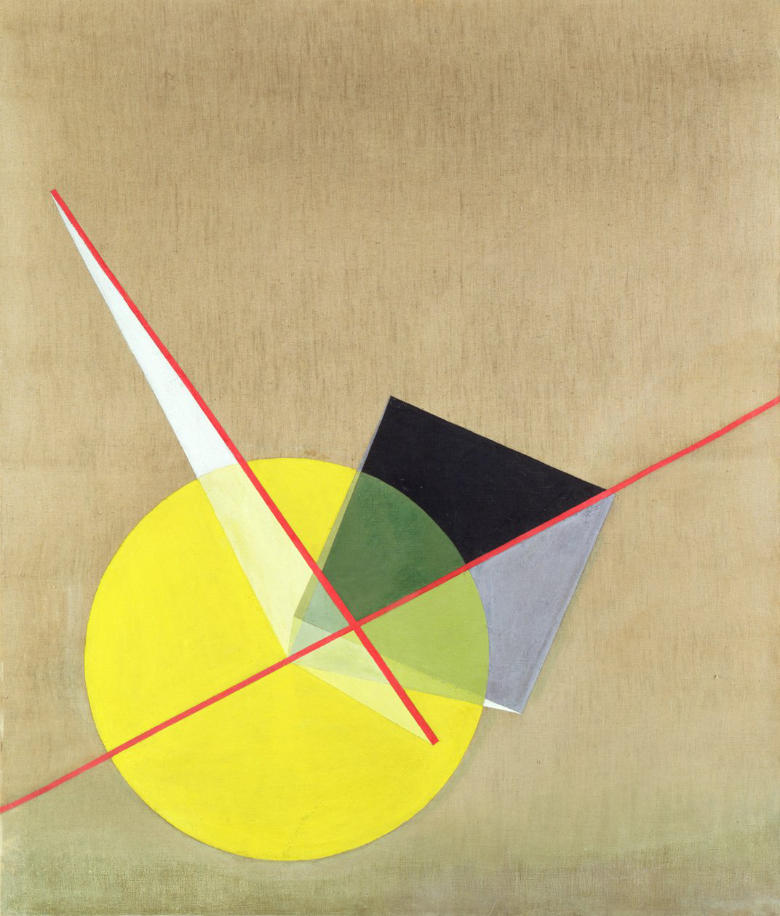

Constructivism is characterised by abstract bold geometric forms and spatial composition with an austere colour palette: basically black, white, red and grey.

Artists used industrial materials. They embraced abstraction, order and function, rejecting traditional aesthetic values in favor of a collective purpose.

Constructivist compositions are striking for their clarity and precision.

Abstract painters often used strong diagonals, linear structures and dynamic asymmetry to create a sense of movement and progress.

Rather than depicting the natural world, they designed it.

The typical artwork resembles a blueprint or a machine diagram more than a painting in the classical sense.

Themes of labor, architecture, revolution and technology reflect the revolutionary philosophy of the Soviet Union.

A time of radical change in Europe

To fully appreciate Constructivism, it’s essential to understand the broader art scene of the time.

The early 20th century was a period of intense experimentation and ideological transformation.

In France, Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, had begun to deconstruct forms into geometric fragments.

In Italy, Futurism celebrated speed, machines and industrial modernity.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the Bauhaus school was emerging with its emphasison functional design and the unity of art and craft.

The Russians shared the Futurism’s obsession with technology and Bauhaus’ fusion of art and function.

While Constructivism adopted certain features of these movements it distinguished itself through its overtly political agenda.

Russian artists were not simply interested in representing the modern world; they wanted to construct it a new, often in direct service to the goals of Socialism and the Soviet state.

Key Artists of Constructivism

Vladimir Tatlin is often considered the father of the movement.

His most famous work, Monument to the Third International (1920), was a towering model of a futuristic spiral structure meant to house the Soviet government.

Though it was never built, it became an icon of the movement, symbolising Constructivism aspirations to reshape the world through architecture and design.

El Lissitzky, painter, designer and architect, brought their ideas to Europe.

His Proun series, combined painting with architectural, blurring the lines between art, engineering and space.

“The artist constructs a new symbol with his work.”

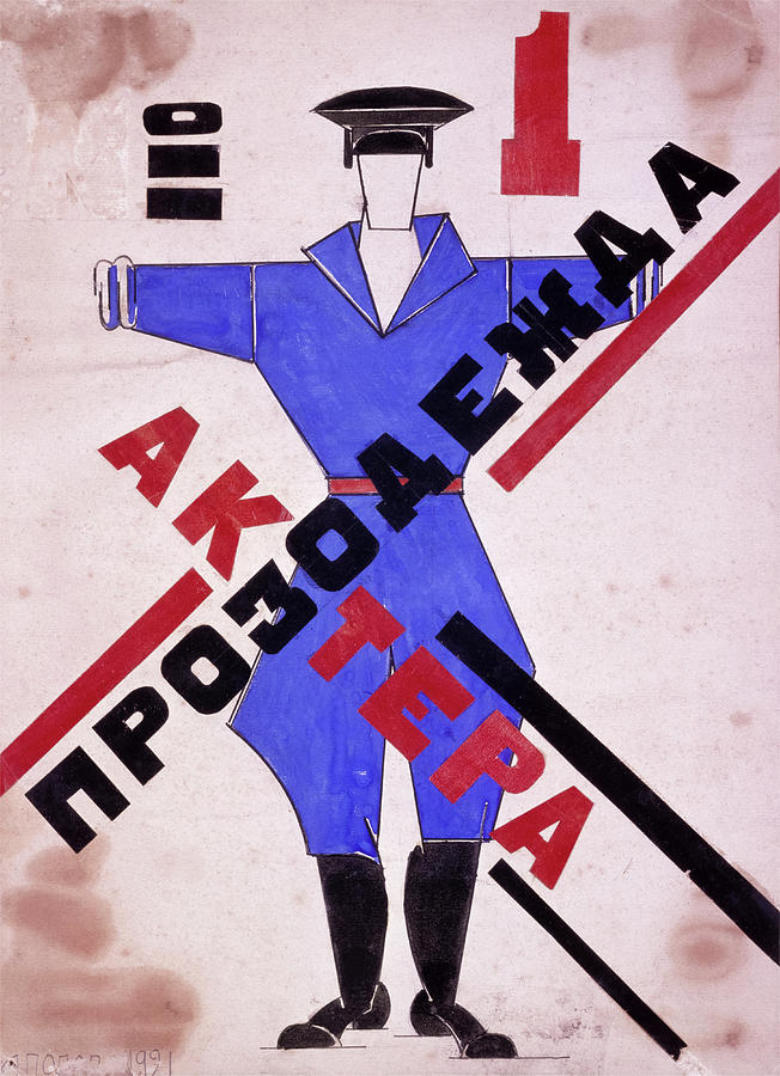

Alexander Rodchenko, a versatile artist and graphic designer, moved away from painting to embrace photography and industrial design.

His work often employed high contrast, sharp angles and dynamic layouts.

His photographic portraits and posters, often created in collaboration with his wife Varvara Stepanova, exemplify their commitment to mass communication and political messaging.

Lyubov Popova was a pioneering female figure in the movement.

Her abstract works fused Cubist and Futurist influences into what she called “painterly architectonics”: compositions that seem to float and shift in space.

She also ventured into textile and stage design, merging aesthetics with everyday life.

Naum Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner developed what they called “Constructive Art” which emphasised clarity and spatial relationships using modern materials like celluloid and metal.

Gabo’s Kinetic Construction (1920), a motorised sculpture, was among the first examples of kinetic art.

Design, Architecture, Theatre

Constructivism was never confined to the canvas. It was inherently interdisciplinary, seeking to permeate all aspects of life.

The movement’s architects envisioned communal housing and public buildings that reflected socialist ideals.

Tatlin, designed clothing and furniture. Popova and Stepanova created textile patterns and theatrical sets.

In Graphic Design, Constructivists revolutionised typography and layout.

Artists like Rodchenko and Lissitzky produced striking propaganda posters, book covers and advertisements, employing photomontage and bold sans-serif fonts to capture attention.

These innovations to disseminate revolutionary messages laid the foundation for modern Graphic Design.

Theatre was another key arena. Constructivist stage designers rejected elaborate historical sets in favor of industrial, abstract structures that highlighted the mechanics of performance.

Directors like Vsevolod Meyerhold collaborated withpainters to create a new kind of theatre: dynamic, physical and socially engaged.

In fashion, their ideas influenced utilitarian clothing designs meant for the new Soviet citizen.

The garments were often unisex, practical and stripped of ornamentation, aligning with the movement’s rejection of bourgeois luxury.

International legacy

Though the style began in the Soviet Union, its influence quickly spread across Europe.

Lissitzky’s collaborations with the Bauhaus and De Stijl Dutch artists helped to bridge ideology with aesthetics.

In Germany, Constructivist principles influenced creations of designers like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

Institutions like the Bauhaus, shared their vision of art as an agent of social change.

However, the movement’s trajectory was short-lived. Stalin cultural policies condemned abstraction and formal experimentation in favor of Socialist Realism.

Many Constructivist artists were persecuted, exiled or forced into different careers. Yet their ideas endured, especially abroad.

Today, the legacy of Constructivism is visible in many areas of contemporary design and architecture.

Its emphasis on minimalism, functionality and geometry can be seen in modernist buildings and urban planning.

In graphic design, the movement’s influence is particularly intense: bold typography, dynamic layouts and use of negative space are still widely emulated.

Motion graphics, corporate identity systems and user interface designs often echo their principles.

Constructivism central idea, that art should serve a social purpose, remains powerfully relevant in today’s art activism and social design.

The belief that design can reshape how we live, work and communicate continues to inspire artists and designers who seek to engage with the political and cultural issues of their time.

Though it was ultimately curtailed by political repression, their legacy endures in today’s built environments, digital interfaces and visual culture.

Constructivism was not just a style. It was a radical rethinking of the role of the artist in society.

Emerging from the heat of revolution, it challenged the idea of art as a passive object of beauty and declared that art must have a function, a purpose.

This philosophy continues reminding us that art has the power not only to reflect the world but to build it.