The reinvention of the object

In 2007 the Victoria and Albert Museum in London organised a memorable exhibition Surreal Things. Today we have the privilege of refocusing on the fascinating theme of this intrinsic symbiosis with a new exhibition: Objects of desire. Surrealism and design. It explores the relationship between the craziest and most daring artists along with one of the most present arts in our lives: design.

La Caixa Foundation and Vitra Design Museum (Germany) present in Madrid an interesting collection of objects and furniture made between 1924 and 2020. This exhibition is a good inspiration for a surrealist exercise: I am going to create my own surrealist collection.

Surrealist Design: Creating Unique Visual Experiences

If I had to choose the objects that best symbolise the explosive cocktail between the surreal and the practical, I would say that Salvador Dalí wins the first three prizes with his sofa with sensual lips, his lobster telephone and his Venus with drawers. These three works inaugurate this very personal selection, it is my modest virtual collection of my 12 favourite surrealist designs, although not all of them are present in the Madrid exhibition.

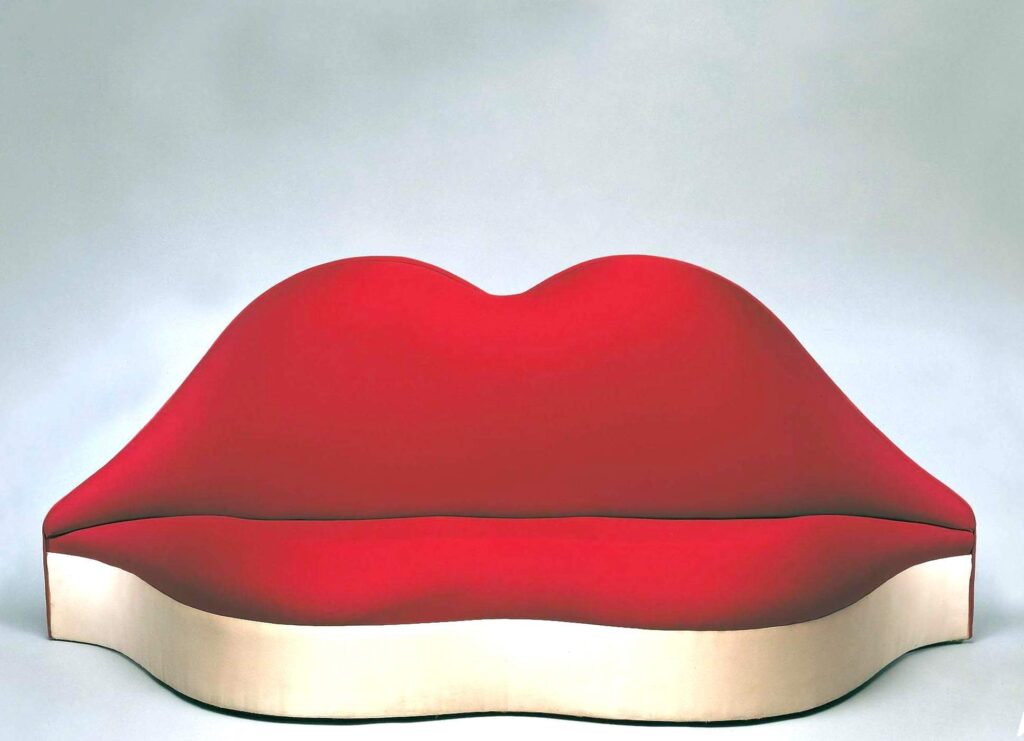

Mae West Lips sofa by Salvador Dalí

Dali’s “Mae West Lips” is a sofa – sculpture in the shape of a woman’s lips and is the center piece of an installation at Dalí Theatre Museum in Figueras. The bright red sized seats, made of foam, covered with a red layer of polyurethane, were molded from the lips of actress Mae West, whom Dalí found fascinating.

Dalí never intended the sofa to have a functional use. He claimed that he based his design on a pile of rocks near the towns of Cadaqués and Portlligat, where he remained for many years with his wife Gala. The sofa was produced in 1973 by Bocaccio Design, also known as BD Barcelona Design. Edward James, a wealthy British patron of the Surrealists in the 1930s, originally commissioned the piece from Dalí. It is now part of the art collections of Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and Brighton Museum (England).

Lobster Telephone by Salvador Dalí

Dali’s “Lobster Telephone” from 1936 is perhaps the most famous example of a surreal object. Also known as Aphrodisiac Telephone, it was created by Dalí in 1936, also for the English poet Edward James.

In the autobiographical book, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, the artist jokingly wrote about his surprise when he ordered a grilled lobster at a restaurant, but was never presented with a boiled phone. It is the quintessential example of a surreal object, formed by the union of elements that are not normally associated with each other, which is both playful and threatening.

Dalí believed that such objects could reveal the secret desires of the unconscious. Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for Dalí. The telephone appears in certain paintings from the late 1930s such as Mountain Lake (Tate Gallery) and the lobster appears in drawings and designs, generally associated with erotic pleasure and pain.

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Dalí created a multimedia experience entitled Dream of Venus, which consisted of dressing live nude models in costumes made from fresh seafood, an event photographed by Horst and George Platt Lynes. The artist used a lobster to cover the female sexual organs of his models. Dalí often drew a close analogy between food and sex. In its original telephone, the tail of the crustacean, where its sexual parts are found, is placed directly on the mouthpiece.

Venus de Milo Drawers by Salvador Dalí

It is a plaster sculpture, created by Dalí in 1936, taking as a reference the famous Roman sculpture Venus in Musée du Louvre (Paris).

This icon of antiquity had fascinated the artist since childhood. In his book The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, he relates that as a child he made a clay copy and how this first attempt at sculpture produced in him “an unmistakable and delicious erotic pleasure”.

Later, in an interview with Playboy magazine in 1964, Dalí explained:

By adding the drawers it is possible to look into the body of the Venus de Milo at the soul: this is how Dalí creates a Freudian and Christian appearance in Greek Civilisation.

Among his many memorable works, perhaps none is more rooted in popular imagination than this Venus with Drawers, a medium-sized plaster reproduction of the famous marble (130-120 BC; Louvre Museum, Paris). Altered with pompoms and decorated drawers on the forehead, breasts, stomach, abdomen and left knee.

The provocative combination illustrates the surreal interest in bringing different elements together to awaken a new reality. For the surrealists, the best means of bringing about this revolution of consciousness was a special type of sculpture that, as Dalí explained in a 1931 essay, was …

… absolutely useless … and created entirely for the purpose of materialising in a fetishistic way, with the maximum of tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delusional character.

Dalí‘s article, which was based on the ideas of Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades, inaugurated the making of objects as an integral part of surrealist activity. Dalí was deeply influenced by the works of Sigmund Freud, stating:

The only difference between immortal Greece and contemporary times is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, purely Platonic in Greek times, is today full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis is capable of opening.

For this surreal object from 1936, Dalí cut out six drawers into Venus, transforming the Greek goddess into a living piece of furniture, a visual pun on the phrase dresser, also known as a desk. Its simple white surface is complemented by elegant leather pulls, a tribute to its beauty and erotic potential. Furthermore, the drawers are a metaphor for how Freudian psychoanalysis opens up the hidden areas of the subconscious. In Dalí‘s words,

Freud discovered the world of the subconscious in the dormant surfaces of ancient bodies, and Dalí cut drawers out of it.

Surrealist furniture by Diego Giacometti

After Dali, I would choose the fun and picturesque furniture by Swiss Diego Giacometti for his. Made in bronze with small animal figurines, they are actually authentic sculptures with practical use.

Diego Giacometti‘s animal- inspired art was rich and varied. Along with familiar animals like cat and dog pets, he liked to depict others that symbolise strength, power, and beauty, such as the heads of lions, wolves, and horses.

Diego was a virtuoso of bronze, a material that allowed him to sculpt with great detail, grace and elasticity. Diego’s animals required special, often expensive techniques, such as the lost wax method. His brothers, the well-known Alberto, a painter and Bruno, an architect, influenced his life and work. With Alberto Giacometti he shared a studio in Paris and artistic projects for decades.

After Alberto’s death in 1966, Diego redoubled his efforts, creating important works for decorators such as Georges Geffroy and Henri Samuel, and sculptural groups for Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Chagall Museum in Nice and Picasso Museum in Paris.

Only then did Diego become recognised as an important artist, until then overshadowed by the fame of his painter brother. An important selection of his work (more than 500 pieces from his studio) was donated in 1986 to Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, after an impressive exhibition held a few months after his death.

Urinary by Marcel Duchamp

Following Dalí‘s example, many other artists began to create absurd contraptions inspired by their subconscious and also new objects built from pre- existing, often obsolete products. These constructions forced new meanings through strange juxtapositions that alluded to dreams or subjective desires.

The best known is the scandalous Urinary by Marcel Duchamp, an eschatological element that the artist takes from a men’s service to elevate it to the category of a work of art. The surrealist object was conceived in part as a critique of consumer culture. However, in creating the real fantastic, using basic products engaging directly with the material world, they also highlighted the commercial possibilities of surrealism and its application in the decorative arts.

In Sigmund Freud’s Dream Analysis theory, the home had a variety of disturbing and sexualised meanings that deeply interested the Surrealists. Combining the old, the new and the strange, they created their own interior environment that offered a stark contrast to the predominant images in modern interior design.

The Surrealists borrowed from the natural sciences of the 19th century, Art Nouveau, and new technologies such as photography and cinema to create a new symbolism, rich in natural shapes and motifs. These works were quickly adapted for use in design, creating a visual language of organic forms, known as biomorphism or free form. Many artists were inspired by the flowing lines and biomorphic shapes of Surrealist art, particularly the work of the abstract sculptor and painter Jan Arp.

Akari Lamps by Isamu Noguchi

A good example is the table and Akari paper lamps by Japanese Isamu Noguchi. In 1951 he visited the city of Gifu, (Japan) known for its manufacture of lanterns and bamboo paper umbrellas. Noguchi designed the first of his lamps to be produced using traditional methods. He called them Akari lamps, which means “light as illumination”, but it also implies the idea of weightlessness.

Akari manufacturing in Japan by Ozeki & Co. since 1951 follows the traditional methods of Japanese Gifu lanterns. Each Akari is handcrafted starting with making washi paper from the inner bark of the mulberry tree. Bamboo ribs run through sculptural moulded wood shapes. The washi paper is cut into strips and glued on both sides of the frame. After the glue has dried and the shape is set, the inner wood shape is disassembled and removed. The result is a sturdy paper structure, which can be folded and flat packed for shipment.

With the warm glow of light projected through the handmade paper onto bamboo frames, Noguchi used traditional Japanese materials to bring modern design into the home. Today his invention of illuminating through paper continues to be copied around the world. In his own words:

Like the beauty of falling leaves and cherry blossoms, Akari are poetic, fleeting, and wavering. All you need to start a home is a room, a tatami, and Akari.”

Table Tour by Gae Aulenti

The Table Tour is one of the most eccentric tables that exist. The piece by Aulenti, is a table on wheels, manufactured by Fontana Arte. This icon of Italian furniture design from the late 20th century is the work of the Italian Gae Aulenti, a brilliant architect, lighting and interior designer, and industrial designer.

She worked in Casabella, a design magazine, and joined her colleagues, rejecting the architecture of masters such as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. They named themselves the Neo Liberty movement, favouring traditional building methods alongside individual stylistic expression.

Tour is a table with a float frosted glass top (0.6° thick). It has four swivel bike wheels, attached to the clear glass deck with stainless steel plates, chrome mounts, and rubber wheels. A real conversation piece for the home or office.

The architect is well known for several large-scale museum projects, including Musée d’Orsay in Paris (1980–86), Contemporary Art Gallery at Centre Pompidou in Paris, Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1985–86) and San Francisco Museum of Asian Art (2000-2003). Gae Aulenti was one of the few women who designed during post-war Italy and created many elegant pieces for Fontana Arte and Martinelli Luce.

Porca Miseria Lamp by Ingo Maurer

The Porca Miseria! Chandelier lamp by the German Ingo Maurer is a revolution with great cunning against contemporary design. It is made up of crockery broken into a thousand pieces. The production of this piece is limited to just ten a year, since the construction of each lamp requires the work of four people who break ceramic pieces with a hammer or simply drop them on the ground. The pieces, arbitrarily broken, determine the arrangement of the final porcelain and metal design. It is manufactured by Maurer GmbH in Germany.

This extravagant lamp is Maurer‘s celebration of slow-motion cinematic explosions, such as those seen in Michelangelo Antonioni‘s film Zabriskie Point (1970). Maurer is an industrial designer specialising in lamp designs and lighting installations. He has been called the poet of light.

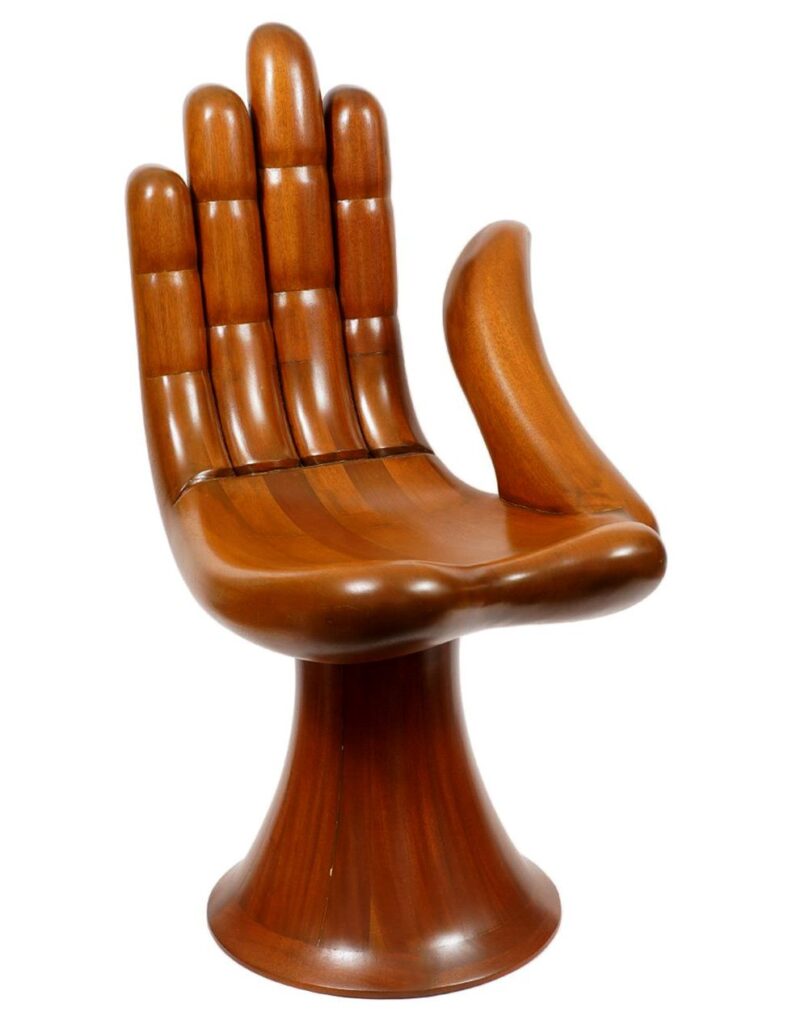

Hand-Chair by Pedro Friedeberg

Hand-Chair is the best known piece by Pedro Friedeberg, a Mexican artist and designer known for his surrealist work full of lines, colours and ancient and religious symbols. Its sculpture – chair is designed so that a person sits in the palm, using the fingers as a backrest and armrests.

Friedeberg began to study architecture but did not finish his studies as he dedicated himself to drawing designs rejecting the conventional forms of the 50s. He designed completely implausible architectural projects such as houses with artichoke roofs. Pedro became part of a group of surrealist artists in Mexico that included Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Frida Kahlo, extremely irreverent, who rejected the social and political art that dominated at the time. Friedeberg had a well-deserved reputation as an eccentric throughout his life. His motto was:

Art is dead because nothing new is produced.

Horse Lamp by Front

Horse Lamp by Front brand is a huge black horse that illuminates us with a luminous lampshade above its head. True to the dimensions of a real horse, it brings a touch of nature in a fairy tale style inspired by sheer madness. His talent for making a bold statement is so well developed that it makes you want to feed the horse carrots.

Without a doubt, this piece becomes what it deserves: to be the maximum center of attention. It is part of the Animal Collection for the Dutch design firm Moooi, which consists of a side table in the shape of a pig and two full-scale models of a horse and a rabbit with lamps on their heads.

Tea-Cup by Maret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim’s Fur-Lined Teacup is another strange and enigmatic surreal object. It consists of a cup with its saucer and spoon, lined with fur, the most absurd of absurdities.

Her subtle wickedness was inspired during a conversation between Meret, Pablo Picasso, and photographer Dora Maar in a Paris cafe. Admiring Oppenheim’s leather-trimmed bracelets, Picasso commented that almost anything could be covered with leather. “Even this cup and its saucer,” Oppenheim replied. In the 1930s, many Surrealist artists arranged found objects in strange combinations that defied reason by evoking unconscious and poetic associations.

Meret was inspired by another object, entitled Déjeuner en fourrure (Breakfast with skins) by the surrealist leader André Breton: a cup and saucer bought from a Paris store that was lined with the skin of a Chinese gazelle. The work evokes the differences in varieties of sensual pleasure: fur can delight the touch but repels the tongue. And a cup and spoon, of course, are made to be put in your mouth.

Wall Plates by Fornasetti

Master of the trompe l’oeil, painter, sculptor, printmaker, interior designer… Fornasetti was the perfect example of a Renaissance-surrealist man. He created 12,000 designs of objects, furniture, 100 models of dishes and even cars. He had craftsman’s hands and a sophisticated eye. Prolific and poetic, he was “the Giorgo De Chirico of Decoration”.

Piero Fornasetti’s wall plates are too beautiful to use as tableware. Observe the eyes that observe you from their magical drawings. The reality is that they are all original surreal works of art to transform the home.

They are featured in the brand’s distinctive motifs, which almost always represent the eternal and enigmatic face of Piero Fornasetti‘s muse, Lina Cavalieri, as well as some with astronomy themes. They are variations on the same theme, but all completely different, the fruit of the exquisite imagination of its creator. They really are works of art wherever they are placed.

This magician of dreams applied his rich imagery of suns, enigmatic faces, hands and classical architectures to any possible support: from dressers to ashtrays, scarves or screens, from fabrics to lamps, umbrellas and plates. His hallmark was black and white, rarely boldly mixed with just two colours. Only two bright shades, gold and red, lit up the grey 1950s of post-war Europe.

He died in 1988 leaving more than 12,000 designs: everyday objects, decorative motifs and printed jewel-pieces that move between Italian tradition and surrealist invention.

The exhibition “Objects of Desire. Surrealism and Design” brings to CaixaForum (Madrid) works by artists such as Salvador Dalí, Man Ray and Lee Miller.

This new exhibit sheds a new light on this fascinating and ongoing creative dialogue, juxtaposing surreal art and design pieces to reveal parallels that have rarely been studied. It also includes paintings, sculptures, collectibles, posters, magazines, books and photographs, as well as historical films.

Surrealist Artists Who Transformed Modern Design

Among the exhibited artists are Giorgio de Chirico, Le Corbusier, Salvador Dalí, Isamu Noguchi, Meret Oppenheim, Gae Aulenti, Björk, Claude Cahun, Achille Castiglioni, among others.

It is divided into four sections. In the first one, he focuses on exploring surrealism from the 1920s to the 1950s, with the application of surrealist principles to painting and its extension to objects, furniture and interiors, fashion and cinema. Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, like his controversial “Urinal”, inspired others like Meret Oppenheim or Salvador Dalí, who created a totally new type of sculpture, with absurd objects from materials and found things. In this first part we find Le Corbusier, Antonio Gaudí, Dalí, Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi and Frederick Kiesler.

The second space of the exhibition includes the image and the archetype. Questions such as Should a thing always be what it seems? Are posed, emphasising the establishment of absurdity, confusion and chance that the surrealists introduce. René Magritte, Achille Castiglione, Duchamp, Gae Aulenti and their table mounted on bicycle wheels are some of the examples.

A third area explores love, eroticism and sexuality that the surrealists incorporate into art. Salvador Dalí, Carlo Mollino, Lee Miller, Dora Maar, Claude Cahun, Man Ray and Elsa Schiaparelli are some of the artists who are passionate about women and eternal feminine eroticism.

The last part is titled Wild Thought. The interest in the archaic, the fortuitous and the irrational is analysed here: Max Ernst and his frottages, Man Ray and his photographs, Joan Miró and his painting The Lion, the Brazilian sculptor brothers Fernando and Humberto Campana and the free-flowing drawings of awareness of Ronan and Erwan Bourollec among its greatest exponents.

The Fusion of Surrealism and Design: A Creative Journey

After the publication of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto was officially launched in 1924, Surrealism quickly became an international intellectual and political movement. Its member artists came from diverse backgrounds and disciplines, such as literature, film, and fine arts. From its birth, everyday objects were a decisive source of inspiration and played a crucial role in its evolution.

Less well known is the decisive impact of Surrealism on design. This has played a major role in liberating design from the functional dogma according to which form follows function. In light of the growing criticism directed at rationalist design starting in the 1930s and especially after World War II, Surrealism broke new ground that addressed emotions, fantasies, fears, and other existential issues.

By the 1920s, the surrealist technique had focused on the use of writing, drawing, collage, and painting as techniques to reveal the subconscious mind. But in 1930 a new type of invention emerged: the creation of the surreal object.

The distancing from text and image was driven by the need to interact directly with the material world, the world of objects and commerce. The surreal object was thought to represent the complexities and contradictions of modern life. In 1940 Salvador Dalí summed up his desire to invent objects as follows:

I try to create fantastic things, magical things, things like in a dream. The world needs more fantasy. Our civilisation is too mechanical. We can make the fantastic real and then it is more real than what really exists.